2025 Monarch Report

14 January, 2026 - Reading time: 6 minutes

This past year the common milkweed growing in our field began sprouting in mid-May and was well up and starting to flower by the time we saw our first monarch in the field on the 2nd of June. These early arrivals were outliers of the main migration which occurred later in June.

I surveyed our field regularly to track the monarch populations and no new monarchs arrived until the last week of June. On the 26th of June we found the first eggs attached to a young milkweed plant and by the 30th we had caterpillars eating milkweed. More monarchs arrived in the field in early July and by mid-month there were eight in my count. We frequently saw the monarchs mating at this time among the monarchs.

The eggs laid in early July yielded a new generation of monarchs in early August. Typically, these new adults are sexually active and lead to more local egg laying and a second jump in the population in September. The first eclosure (emergence from its chrysalis) was on 28th July, a month after the first egg was seen. This agrees with the expected one-month period for a monarch to develop from an egg. The dynamics in our field milkweed this year is shown in the following chart at the top of the page..

Normally, the sexual activity in early July would lead to an abundance of egg laying followed by an abundance of caterpillars in the field during the month. This year that did not happen because just then the long, hot, dry spell began. During July, August and September the Kentville rainfall was only 68 mm—the average in a normal year is 245 mm. The milkweed normally continues to send up more young plants, which we encourage with controlled mowing. It is on these small plants that the caterpillars eat and grow. This year the milkweed stopped sprouting, and we experienced reduced caterpillar activity. The drought slowed the monarch development but did not stop it. The number flying in the field varied and reached a maximum of 19 on the 23rd of August, down from previous years.

The monarchs that emerge after mid-August are in the state of diapause, meaning that they are not sexually active and ready to begin their migration south. After that date, the numbers in the field decrease as they leave the area. The last monarch was seen in the field on 28th September, which is a bit earlier than usual. In 2024, the last monarchs left on 15th October. Due to the drought, the red clover and goldenrod flowers in our field dried out early and provided little nectar in late summer, which the monarchs typically use to ‘bulk up’ on in preparation for their flight south. Also, the milkweed plants were dropping leaves and some attached chrysalises were lost before the monarchs could emerge.

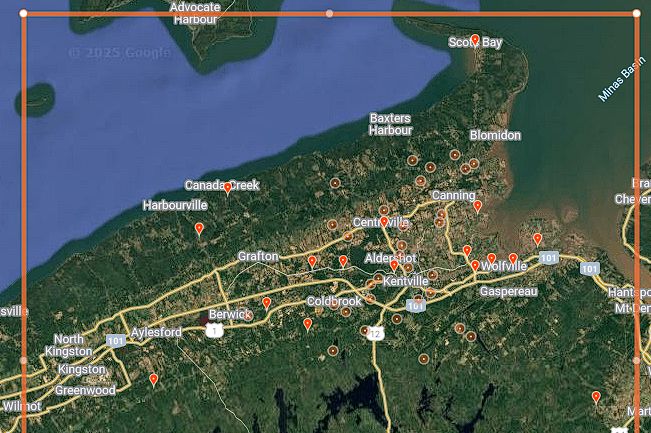

We enjoyed the presence of the monarchs all summer. In contrast, I encountered only a few outside of our field. To get an estimate of the wider population of monarchs, I accessed observations on iNaturalists (iNaturalist.org) and the map here shows the locations of the observations reported in 2025 in Kings County, Nova Scotia.